Thou shall pass?

TL;DR

Reverse executable that uses clever function renaming techniques

Description

This was a challenge from the X-MAS CTF 2020. It was the easiest one in the Reversing category but I still think it was pretty fun because it introduced me to an interesting obfuscation technique.

Challenge Description

For thou to pass, the code might not but be entered

Author: Th3R4nd0m

The challenge provides us with a simple ELF binary to run

Basic Dynamic Analysis

Let’s run the binary and see how it works:

./thou_shall_pass

Thou shall not pass till thou say the code

X-MAS{test}

Thou shall pass! Or maybe not?We can see that the program asks us for input, then checks it and based on those checks probably returns either true or false.

A first thing we can do to see what the binary is doing is to run ltrace and see which library functions the program calls:

ltrace ./thou_shall_pass

ptrace(0, 0, 0x7ffdce31de58, 0x7f1b479c9718) = -1

printf("Pls no") = 6

exit(1Pls no <no return ...>

+++ exited (status 1) +++Here we can see the first anti-analysis measure, a call to ptrace which basically tries to attach itself as a debugger on the running process. This call fails when there’s already a debugger attached (in our case ltrace) and returns -1. The program detects that and prints “Pls no” and aborts. To solve this, we can patch out the call to ptrace or do something else so the program doesn’t exit. Let’s have a look at where the binary calls ptrace. I’ll be using radare2 throughout this writeup as I think it’s a great reverse engineering tool for dynamic analysis as well as ghidra for a more high-level overview of the source code

Locating ptrace

This binary has been stripped, which means that all symbols that don’t have anything to do with dynamic linking have been removed. Basically, the only function or variable names that still remain are those from external libraries like strcmp or printf.

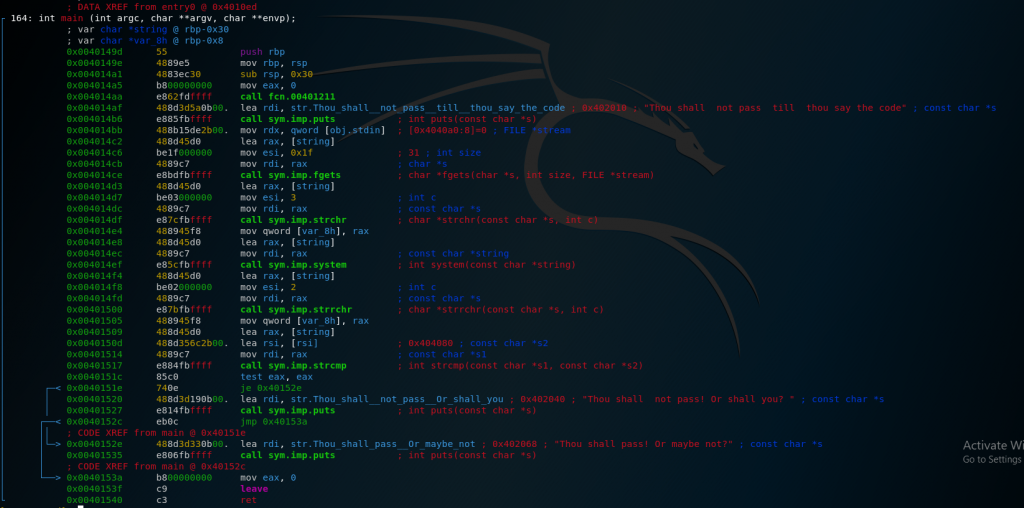

Let’s take a look at the main function for our binary:

As we can see here, the main function is rather short but seems to contain a lot of library calls but we can’t find a call to ptrace. The only other function we can find is a call to fcn.00401211 so let’s take a look at that.

Here we can see the call to ptrace, followed by a check whether rax is zero. Let’s patch that check out so we don’t exit when we debug. As we can see, the binary uses jns (jump if not sign) to check if the result of the call to ptrace is negative and then skips the exit routine if it isn’t. To patch this, we’ll just replace the opcode for jns (0x79) with the opcode for jmp (0xeb) and we can finally debug our program.

Further dynamic analysis

Now that we can use ltrace, let’s see what we can find:

ltrace ./thou_shall_patch

ptrace(0, 0, 0x7fffd0fc3248, 0x7f988bddf718) = -1

puts("Thou shall not pass till thou"...Thou shall not pass till thou say the code

) = 46

fgets(X-MAS{test}

"X-MAS{test}\n", 31, 0x7f988bddf980) = 0x7fffd0fc3120

strchr("X-MAS{test}\n", '\003') = "\003\004\005\006\a\b\t\n\v\f\r\016\017\020\021\022\023\024\025\026\027\030\031\032\033\034\035\036\037 !""...

system("\302ij\n\232\333\243+\233\243\353P") = -788778691

strrchr("\307om\002\223\321\250'\226\255\344@\021\022\023\024\227\276\025\030\031\032\033\034\233\236\035 !"", '\002') = "\002\003\004\005\006\a\b\t\n\v\f\r\016\017\020\021\022\023\024\025\026\027\030\031\032\033\034\035\036\037 !"...

strcmp("\361\333[\200\344t*\311\245k9\020D\204\304\005\345\257E\006F\206\306\a\346\247G\bH\210", "\373\321Q\212\356~Ti\233ow\260\200\356p\301)gq\344\234\352r\355\223_\021\352\244x" <unfinished ...>

strncmp("\373\321Q\212\356~ \303\257a3\032N\216\316\017\357\245O\fL\214\314\r\354\255M\002B\202", "\373\321Q\212\356~Ti\233ow\260\200\356p\301)gq\344\234\352r\355\223_\021\352\244x", 31) = -52

<... strcmp resumed> ) = 0

puts("Thou shall pass! Or maybe not?"Thou shall pass! Or maybe not?

) = 31

+++ exited (status 0) +++We can see several calls to C library functions like strchr and strcmp that apparently change our string. However, we can see that the call to strchr (which normally returns the first occurence of a substring in a given string) doesn’t even return a number but instead takes our input and seems to transform it into something longer.

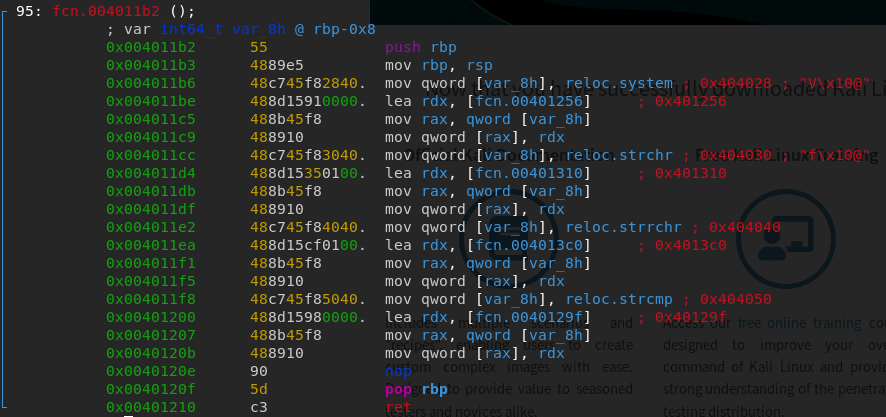

Let’s investigate the function we saw earlier that gets called after the ptrace check, fcn.004011b2:

Something interesting happens here. Basically, the program loads the addresses of 4 library functions, system, strchr, strrchr and strcmp into rax, then loads the addresses of 4 other functions into rdx and finally replaces the library function addresses with the 4 other functions. (These addresses are saved in the GOT, the Global Offset Table). This means that every time one of those library functions gets called, the binary actually calls one of the other 4 functions. This also explains why the call to strchr produced such a weird result. The way forward should seem clear now, we need to reverse each one of the four functions and see what they are doing. So let’s start doing that:

strchr

In the following cases, I’ll use ghidra to simplify the task a bit. When I was originally solving the challenges, I was using a combination of the decompilation provided by ghidra together with dynamic analysis with radare2 to check my findings. For the strchr function, ghidra gives us:

while (local_c < 0x1e) {

local_10 = 0;

while (local_10 < param_2 - ((int)(uVar1 << 3) - (int)uVar1)) {

*(byte *)(local_c + param_1) =

*(char *)(param_1 + local_c) * '\x02' | *(byte *)(param_1 + local_c) >> 7;

local_10 = local_10 + 1;

}

local_c = local_c + 1;

}

return;This is a lot of code and it’s also not that easily readable so I’ll talk you through it. Basically, the code loops over each character provided to it as param_1 (our input). For each character it does param_2 iterations (param_2 is always 3 in our case) of the following procedure:

It multiplies the char by two, then ORs it by the character’s value shifted to the right by 7. This means that if the character is bigger than 0x7F (binary: 0111 1111 >> 7 = 0000 0000), we add 1, if not we add nothing. This process is easily reversible, following the python decryption code that takes as input a hex string (excuse my laziness, I actually just generated a lookuplist for each input character):

dictionary = {}

for i in range(40,128):

char = chr(i)

encrypted = encrypt(char,3) #encrypt is an implementation of the encrypt routine described above

dictionary[encrypted] = char # you can find the code for the encrypt function in the PS section

def decrypt(strings):

result = ""

for i in range(len(strings)//2):

char = strings[i*2:i*2+2]

try:

result += dictionary[char]

except KeyError:

result += "?"

return resultNow we can reverse the first encryption function, so on to the next

system

Again, decompiled ghidra output:

while (local_c < 0x1e) {

*(byte *)(param_1 + local_c) = *(byte *)(param_1 + local_c) ^ (char)local_c + 5U;

local_c = local_c + 1;

}This time, the code is really short and easy to understand. It loops over the input array and xors each value with 5 + the iteration. This means that the first char is xored with 5, the second with 6 and so on.

Here is the decryption routine implemented in python:

def decrypt2(strings):

result = ""

for i in range(len(strings)//2):

char = strings[i*2:i*2+2]

number = int(char,16)

number = number ^ (i+5)

if len(hex(number)) < 4:

result += "0" + hex(number)[2:]

else:

result += hex(number)[2:]

return resultThe function again expects a hex string as parameter and the small construct at the end makes sure that each hex output is also two chars long (This caused me a few headaches when I couldn’t get the correct output).

Alright, on to the next encryption.

strrchr

ghidra:

while (local_c < 0x1e) {

local_10 = 0;

while (local_10 < param_2 - ((int)(uVar2 << 3) - (int)uVar2)) {

bVar1 = *(byte *)(param_1 + local_c);

*(byte *)(param_1 + local_c) = *(byte *)(param_1 + local_c) >> 1;

*(byte *)(param_1 + local_c) =

*(byte *)(param_1 + local_c) | (byte)((int)(char)(bVar1 & 1) << 7);

local_10 = local_10 + 1;

}

local_c = local_c + 1;

}

return;This part also isn’t too hard. The code basically does some bit-shifting. For each iteration, which is defined by param_2 which in our case is always 2, it takes an input byte, shifts it one to the left and then puts the lowest bit of that input byte in the highest bit place. As an example, we can take 0xA7 which is 1010 0111 in binary. The resulting binary number after the bit shifting would be 1110 1001 which is 0xE9 in hexadecimal.

A decryption function in python could look like this:

def decrypt3(strings,loops):

result = ""

for i in range(len(strings)//2):

char = strings[i*2:i*2+2]

number = int(char,16)

for i in range(loops):

left = number & 0x7F

left = left << 1

right = (number & 0x80)>>7

number = right + left

if len(hex(number)) < 4:

result += "0" + hex(number)[2:]

else:

result += hex(number)[2:]

return resultThis just shifts the bits in the opposite direction and again expects a hex string as input.

strcmp

We’re now close to the finish line, the only function that still needs to be analyzed is strcmp. ghidra gives us:

while (local_c < 0x1e) {

param_1[local_c] = param_1[local_c] ^ 10;

local_c = local_c + 1;

}

iVar1 = strncmp(param_1,param_2,0x1f);

return (ulong)(iVar1 == 0);

}Again quite a short function, that does a little bit of encryption as well as the final check.

First, the encryption that is done here is a simple xor with 10 on each character, easily reversible with the following code:

def decrypt4(strings):

result = ""

for i in range(len(strings)//2):

char = strings[i*2:i*2+2]

number = int(char,16)

number = number ^ 10

if len(hex(number)) < 4:

result += "0" + hex(number)[2:]

else:

result += hex(number)[2:]

return resultAfter that, the binary calls strncmp which compares two strings for a given length, in out case a length of 0x1f. The function then checks if the output is equal to zero, so if the two strings are equal and returns to main.

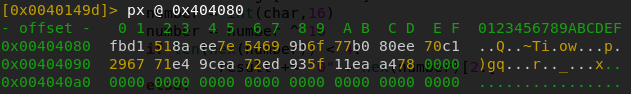

What we need to do now is to extract the string it’s compared against, we can find in the main function that it’s located at 0x404080. In radare, the memory at that address looks like this:

Having that we can finally solve the challenge by chaining the decryption calls. In my example, the code looked like this:

encoded = "fbd1518aee7e54699b6f77b080ee70c1296771e49cea72ed935f11eaa478"

print(decrypt(decrypt2(decrypt3(decrypt4(encoded),2))))Running this gives us the flag X-MAS{N0is__g0_g3t_th3_points}

Summary

Great challenge to start off the CTF even though it was already quite tough for only 50 points. In general, the challenges in this CTF were way harder than at any others I had previously participated in but it was nice to just be tenacious and not give up even if it took more than 5 hours to finally get the solution (one of the other challenges in this CTF). The next writeups won’t go into this much detail, I just always think it’s nice to explain the first challenge extremely clear so people that couldn’t solve it can learn new stuff and tackle it at the next CTF.Hope you liked this writeup

-Trigleos