Da French?

TL;DR

Reverse executable that uses AES encryption and decrypt network traffic

Description

This was one of the harder challenges for the XMAS-CTF 2020 and I actually managed to be the third one that solved it. In the end, the challenge only had around 15 solves, which shows that many people did not see that the binary was using AES encryption. The challenge gives us an ELF executable as well as a network capture which we can use to solve the challenge

Network capture

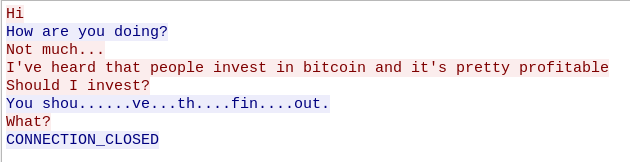

When we open final.pcap (the provided network capture) we can see two TCP streams. The first one looks like this:

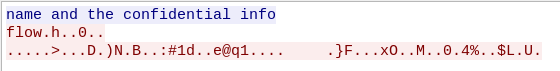

Not much to see here, except that the connection kind of drops at some point. This is where we can find the packets for the second TCP stream which looks like this:

Now this one looks more interesting. It starts off with some readable text, however most of the rest is illegible, which shows us that probably some kind of encryption was involved. We cannot extract any more information out of the pcap file at this point so let’s tackle the executable.

Basic Dynamic Analysis

First of all, when we run the binary, nothing seems to happen. If we investigate it with strace, we get the following output:

socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_IP) = 3

connect(3, {sa_family=AF_INET, sin_port=htons(1337), sin_addr=inet_addr("111.161.162.163")}, 16We can see here that the executable tries to connect to a server sitting at 111.161.162.163 on port 1337. Because we don’t have access to that server, let’s patch the binary and make it connect to 127.0.0.1 (the localhost address) so we can interact with the program by spinning up a listener on port 1337.

After that, the executable waits for input from the remote end and exits if we give it some random input. Let’s try to find out what we need to put in so the executable keeps running.

Disassembly

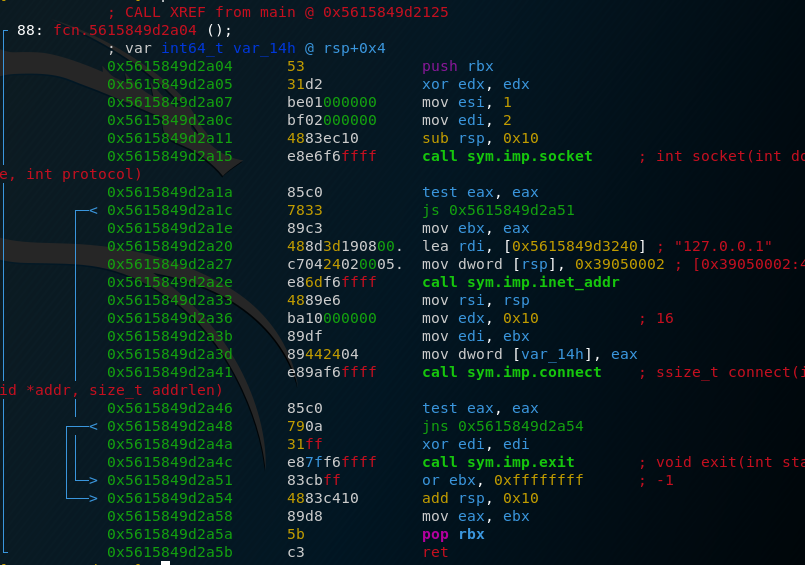

The executable first calls a user-defined function. If we take a look at it, we see that this function connects to the server.

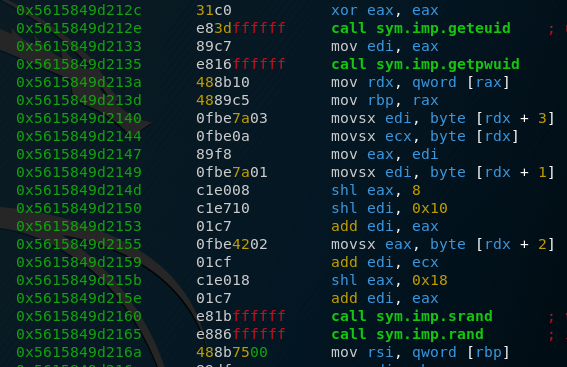

After that, we have calls to geteuid, getpwuid, srand and rand (further analysis of this will be done further down).

Then we have another call to a user-defined function which looks like this:

What we have here are the calls to recv and then after that a call to strcmp. If we check what our input is compared against, we find the string “name and the confidential info\n”. This is also the string that we found earlier in our network capture, so we know that the second TCP stream was established by our executable. The code goes on and sends something to the remote end, in my case this was the string “root”. Now that we have this information, let’s see what the earlier library calls achieved.

Generation of seed

geteuid is a call you don’t see that often in programs. It returns the user ID of the calling process. In my case, it was 0. getpwuid on the other hand takes a user ID and returns the associated entry in the /etc/passwd file. This means that it returns the username, the user shell as well as other stuff for the calling process. After that, the process takes the first 4 bytes of the output of getpwuid (the first four characters of the username) and combines them into a single value by shifting them and adding them together. For example, it takes the third character and shifts it by a value of 0x10 to the left. If we take the username root as an example, we get a generation that looks like this:

r o o t

0x72 0x6F 0x6F 0x74

bit-shifting and adding together:

o o t r

0x6F6F7472Here’s the implementation of this generation in python:

def seed_username(name):

fourth = ord(name[3])

fourth = fourth << 8

first = ord(name[0])

second = ord(name[1])

third = ord(name[2])

second = second << 0x10

third = third << 0x18

sum_1 = second + fourth + first + third

return sum_1After that, the executable simply seeds the pseudo-random generator with this value and calls rand() once. We now also know what the executable sends to its remote server. It’s the username for the calling process which means that in the case of the packet capture, the username was flow. (This will be important later on)

Further disassembly

We can now take a look at the bottom half of the main function.

We can see a simple decryption stub that xors some string that’s stored in memory, then calls a function with that string as an argument. If we use dynamic analysis, we quickly find that the encrypted string reads ./confidential. The function that uses it is also rather simple:

It basically just opens a file named confidential in the current directory, reads it and then returns to main. The last thing we have to analyse is the last function call before the end of main.

Encryption

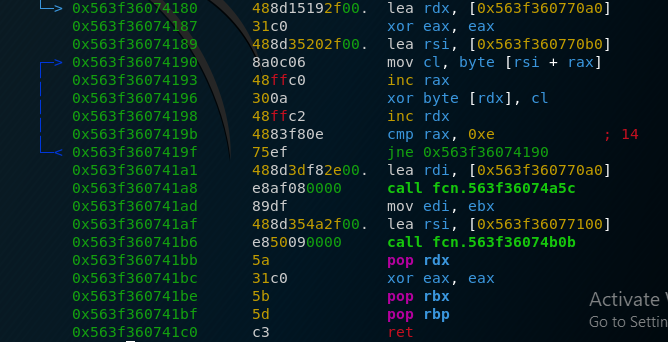

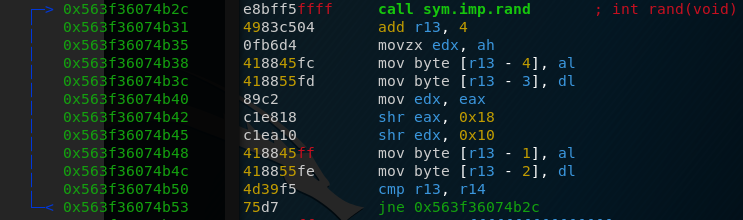

Unfortunately, this is by far the longest and most complicated function in the program but we’ll go through it step by step to understand it. The first thing that we need to understand is the following bit of code:

This loop executes four times and each time generates a new random number. After doing that, it basically turns the generated number around. The last byte becomes the first byte, the second byte becomes the second last byte and so on. Here’s a sample implementation in C that generates four random bytes:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main()

{

srand(1869379430); /*seed for username:flow*/

rand(); /*first random is not used*/

printf("%x ", rand());

printf("%x ", rand());

printf("%x ", rand());

printf("%x\n", rand());

}And here’s the python implementation that takes these four random numbers and flips them around:

randoms = "56e6ebe3 023e65c2 0f1a8ae0 6b9d0011" #random numbers you get when you use flow as a username

def first_line(random_numbers):

liste = random_numbers.split(" ")

supere = ""

for number in liste:

result = ""

result += number[-2:]

result += number[-4:-2]

result += number[2:4]

result += number[0:2]

supere += result

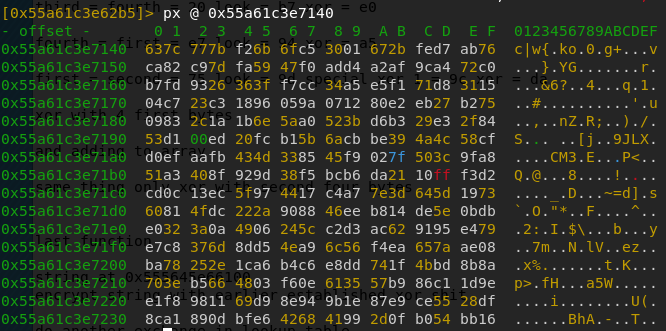

return supereAfter doing some more operations, the executable calls another function with our earlier generated four random numbers as an input. This function is in fact the AES key schedule algorithm. Before I went into this CTF, I’d heard of AES but I never actually knew how it worked or the actual details of it. So I painstakingly tried to understand the whole algorithm and I even rewrote it in python without knowing that it was AES. I managed to entirely reverse the key schedule algorithm, however the next part of the function was a call to the encryption routine of AES which employs a lot of lookup tables and bit shifting, so it was nearly impossible to keep track of everything that was happening. At that point, I took a break which gave me the idea that this whole algorithm could be AES. After taking a look at what lookup table AES used, I was able to find the same table in the executable’s memory, also known as Rijndael S-box:

There were some other ways you could detect that the executable was using AES. For example the key schedule algorithm returned 11 16-bytes keys (our old key and 10 new keys) which were later used in the 10 AES rounds. At some point, the executable was padding the text contained in ./confidential to have a length of 16 bytes (AES operates on blocks of 16 bytes)

Decryption

After realizing that the program was using AES, I only had to find out what key and mode were employed. I already knew that the key used were the four random bytes shifted around which also added up to a length of 16 bytes, one of the possible key lengths for AES. I guessed that the program was using the ECB mode and tested this by running a few tests in python with the username root and trying to decrypt the output that the executable gave me with the generated key. After all of this was successfull, I generated the key for the username flow which turned out to be e3ebe656c2653e02e08a1a0f11009d6b. After having all of this, the solution of the challenge was trivial. Extract the encrypted content from the packet capture, put it into a python script and run it to get the solution. Here’s my python script:

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

key = b"\xe3\xeb\xe6\x56\xc2\x65\x3e\x02\xe0\x8a\x1a\x0f\x11\x00\x9d\x6b"

print(key)

cipher = AES.new(key,AES.MODE_ECB)

ciphertext = b'\xbd\x68\x96\x01\x30\xa6\x1e\x0d\xce\x86\xf0\xbb\xf9\x3e\x05\x94\xbc\x44\x00\x29\x4e\xa5\x42\x13\xea\x3a\x23\x31\x64\x1f\xfb\x65'

ciphertext += b'\x40\x71\x31\xd6\x9f\xd2\xc2\x09\xa6\x7d\x46\x8d\x8c\x85\x78\x4f\xd2\xee\x4d\xd8\x02\x30\xab\x34\x25\xc5\xb4\x24\x4c\xc6\x55\xd6'

print(cipher.decrypt(ciphertext))Running this finally gives us the flag X-MAS{d0nt_buy_bitcoin_cause_th3_bogdanoffs_will_find_out}

Conclusion

I really liked this challenge as it was hard but at the same time not impossible to solve. It taught me great lot about AES and its exact inner workings and even though solving this challenge took me around 6 hours and I was close to giving up at multiple points, I managed to get through. Tenaciousness ultimately often pays off in CTFs and I still sometimes give up too early because it gets too hard but I hope I will see challenges through more often now. Hope you liked this writeup.

-Trigleos

Thank you!!1