castorsCTF2020

TL;DR

Investigating a Ransomware attack and try to reverse the process

Description

Ransomware has been an increasing problem for companies as well as normal internet users. Criminals use malware to encrypt files on your computer and they’ll only give you the decryption key if you transfer them a specified amount of money. castorsCTFs Ransom challenge had a similar approach, with the only difference that the encryption used here was easily reversible by investigating the executable as well as the recorded network traffic. It still was a very fun challenge and taught me a lot about investigating Linux malware.

Basic investigation

The challenge gives us the encrypted flag.png file as well as a ransom executable and a network capture.

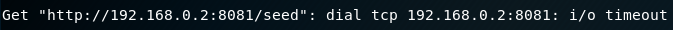

Let’s first investigate what the executable does by running strings and ltrace on it and record any significant discoveries. strings returns a lot of data and it is kind of hard to get anything out of it. ltrace however stops at one point and returns valuable info:

We can see here that the executable tries to contact a server sitting at 192.168.0.2 using the http protocol trying to get the page /seed. Currently, that server seems to be down however. So just by running a simple ltrace, we’ve alround found the C&C server. Now let’s open up the executable in radare2 and take a look at the precise inner workings

Reverse Engineering

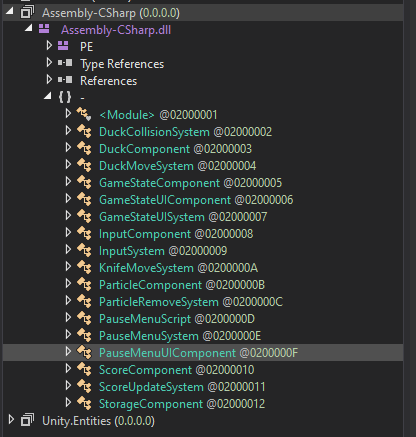

Looking into the executable’s main function, we find sym.main.getSeed, sym.main.send, sym.main.encrypt and sym.main.main. So let’s start at sym.main.main

(Tip:if you don’t want to wait for radare to finish analyzing every function because that can take some time, just go to sym.main.main and define a function at that address using af, in my case the exact command was af @ 0x00640730)

sym.main.main

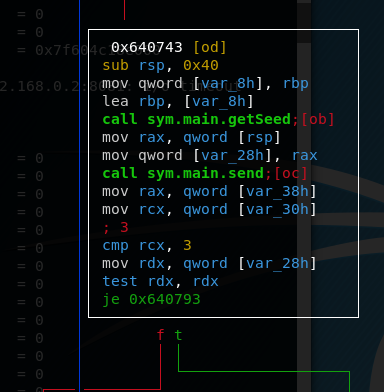

Let’s check how this function starts. Ignoring the memory allocation at the beginning, the executable starts off with a call to main.getSeed and after that a call to main.send

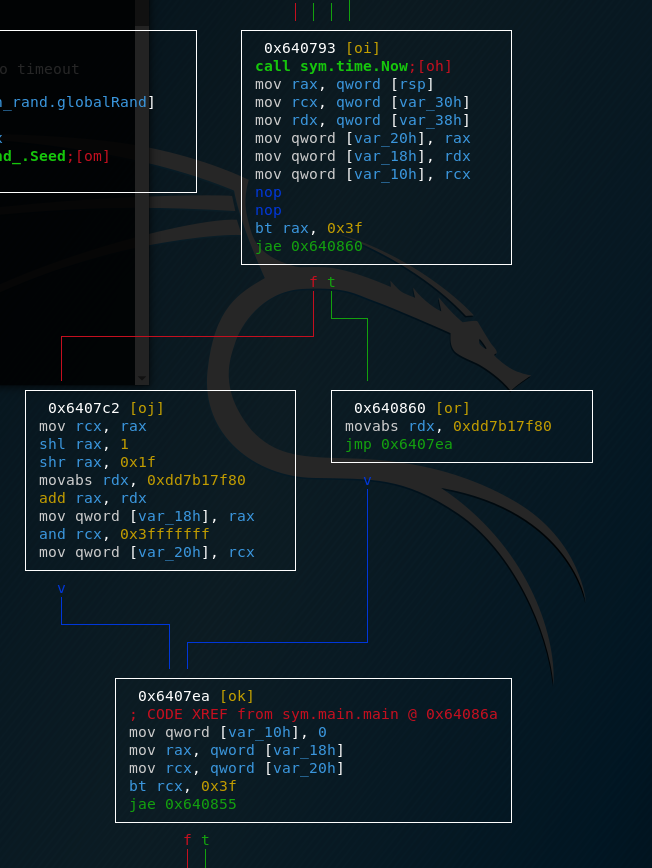

After that the program does a few checks to examine the results from the previous function calls. By quickly analysing the aftermath of the call to sym.send we can assume that sym.send returned two variables on the stack, var_38h and var_30h and sym.getSeed returned one, var_28h, and that they got put into rax, rcx and rdx respectively. The first check that is performed is checking if rdx is zero. If yes, the flow goes to the “failed” part (trust me on this). rdx probably contains the seed value

from the main.getSeed function so the test just checks if getSeed finished successfully.

On to the next checks:

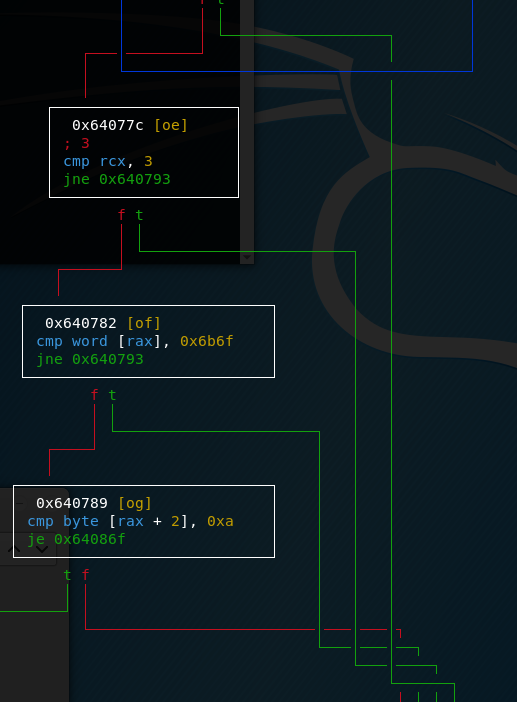

First of all, rcx is compared to three. We can’t yet do that much with that information so let’s leave it. After that the two bytes that are saved where rax points to are compared with 0x6b6f. When something has a 6 or a 7 as first digit, always check if it might be ASCII. In this case, 0x6b6f = “ko” and, considering endianness, this might spell “ok”. Check number three compares the third byte stored at rax with 0xa, the return character. Now we also understand what rcx stands for. It probably contains the length of the string that we got send so rax contains the string we got send. In a nutshell, the executable checks if sym.send gave us the string “ok”, if not flow goes to the “failed” branch. But let’s first check what happens if the flow goes to the “success” branch:

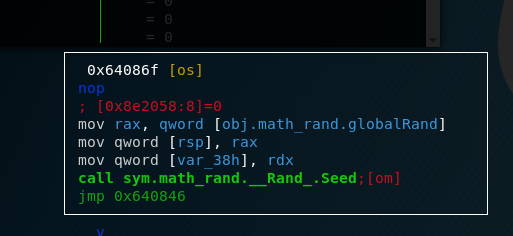

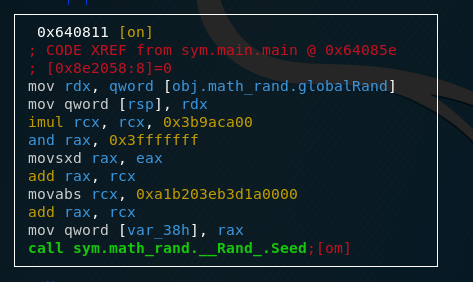

The logic here is quite easy, the executable just calls a math.Rand.Seed function, probably with var_38 as an argument, which now contains the value saved in rdx which, as we established earlier, is the result from the getSeed function. So let’s go on to the failed branch.

Without going to much into detail, the program calls time.Now which returns the current time, then performs some transformations on it and finally also calls math.Rand.Seed

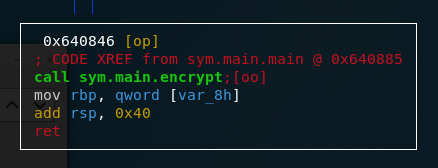

In the end, both program flows come back together and main.encrypt is called.

To verify our claims, let’s have a quick look into main.getSeed and main.send

sym.main.send and sym.main.getSeed

Without going to much into details, in main.getSeed we get a call to net_http._Client.Get which has http://192.168.0.2:8081/seed as one of its arguments. This is the point we noticed earlier, where the executable tries to contact its C&C server. Continuing the analysis, we can find a few calls to string manipulation functions as well as a call to Atoi which converts a string to an integer.

sym.main.send is as well quite big but one thing to notice are the call to sym.net_http._Client.Post with the C&C server as an argument.

So now let’s finally look at main.encrypt

sym.main.encrypt

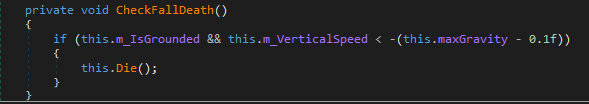

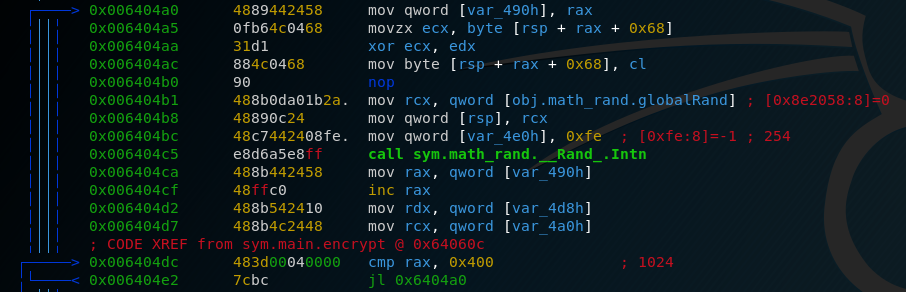

Again, a pretty big function but let’s focus on the essential. A call to Rand.Intn which probably returns a random integer after we’ve set the seed earlier in the main function. Several calls to os.File.Read, os.File.Write and os.OpenFile with flag.png as an argument. But the important part of the function happens in a very short area.

So let’s go through this systematically. We have an iterative variable var_490 which is increased by one and is compared against 1024. We have a structure on top of the stack that is xored with a value stored in edx. And we have a call to math.rand.Intn which has the value 254 as an argument, probably the range of random numbers that we want (254 is exactly one byte). Now let’s assume that the result from that call to Rand.Intn gets put into rdx. In summary, a structure on top of the stack gets xored 1024 times with a random integer between 0 and 254. After this part we can see a call to File.Write so we can assume that the result is written to the flag.png file. We now have everything we need from the executable so let’s summarize our findings.

Executable summary

The executable contacts the C&C server for a seed, if it doesn’t get one, it calculates it own based on the current time. After that, it sets the random function to that seed and calls the encrypt function which opens and reads the flag.png file and xors it byte by byte with a random integer between 0 and 256. The result is then written again to the flag.png file. A thing to note here is that random never means truly random in computer world. We use the term pseudo-randomness in this context. Pseudo-randomness functions in a way that a “random” function gets seeded and based on that seed calculates each random value. In many programming languages, the programmer doesn’t have to specify a seed, if the random function is called without an argument, the compiler just uses the current time as seed. A last thing to gain from this executable is to determine which programming language was used, because different programming languages use different random number generators and we need to find the right one if we want to get the same numbers later to reverse the process. This actually took me some time because I just assumed it to be C but if you search up the function names such as Fprintln or Rand.Intn you soon find references to Golang. If you look at strings within the executable, you can also find a lot that hint towards the use of Go so that’s what we’re gonna go with.

I’ll finish the solution of this challenge in the next part, because this post is already quite long and complicated. I wanted to give a detailed look into the process of reverse engineering a ransomware because writeups often assume a certain base knowledge and I tried here to explain every single little step that can be taken to get to the solution

-Trigleos